Orbiter X

You don't really tend to get very many people talking about archive BBC radio sci-fi. In fairness, that's probably because there's never really been that much of it to talk about.

Well, in fairness, there's been quite a lot of it, just very little that is actually widely known about. Leaving aside the possibly unresolvable question of whether The Hitch-Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy counts as 'sci-fi drama' or not, there are indeed a couple of well-remembered and widely-loved examples; the original atom age Light Programme cliffhanging serial Journey Into Space, Radio 4's lengthy post-microchip 'intelligent sci-fi' cult favourite Earthsearch, and the same station's superlative adaptations of The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings (the former, incidentally, almost shorter in its entirety than the first part of Peter Jackson's bloated big-screen reading).

Beyond these there are a handful of shows with minor but significant appeal to fans of other genre favourites; Nigel Kneale's largely forgotten nineties postscript The Quatermass Memoirs, serials and plays by Doctor Who writers including Victor Pemberton's The Slide and Robert Holmes' Aliens In The Mind, and a late sixties version of The War Of The Worlds with music from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's David Cain. And beyond these, there are hundreds if not thousands that came and went and thrilled a few million listeners before being almost completely forgotten.

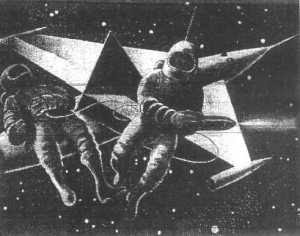

Broadcast once by the Light Programme late in 1959, Orbiter X was a relatively straight-laced serial inspired by recent scientific developments in the 'space race', which was then at its most intense and confrontational. Running to fourteen episodes on Monday evenings between 28th September and 28th December, the storyline was based very closely on theoretical plans for an orbiting 'refuelling station' that would enable rockets to travel deeper into space than was then physically possible. However, this wasn't the only topical aspect to the serial; while it was carefully and diplomatically disguised with less contentious character and place names, there was a definite tinge of Cold War paranoia in the unfolding storyline.

You would be forgiven for expecting the action to take place on board Orbiter X itself, but at the start of the series it hasn't even been built yet. A rocket carrying a team of experts who were due to supervise the construction process has gone missing, prompting Captain Britton and his assistants - more inquisitive than intrepid - to set off on a rescue mission. On arriving at the station's intended location, they are greeted by an unidentified spacecraft, and discover that they've been led into a trap; someone - who may or may not be from Earth - has plans for Orbiter X that go way beyond doling out a bit of additional rocket fuel. Brilliantly, the audience must have been as surprised by this as the characters were; the sizeable Radio Times article that accompanied the first episode cunningly only suggested that the series would examine the emotional and technological impact of working in a vacuum.

Produced by Charles Maxwell, a name more normally associated with radio comedy (most notably commissioning the phenomenally popular sketch show I'm Sorry I'll Read That Again), Orbiter X was written by prolific radio dramatist B.D. Chapman. Previously a lead writer on Dick Barton - Special Agent, Chapman had deliberately devised the serial to appeal to a family audience rather than just flying saucer-obsessed youngsters, and saw the scientific plausibility and topical concerns as key to achieving this; indeed, Chapman only half-jokingly told Radio Times that he was concerned some aspects might be overtaken by reality ahead of transmission. Hammer Films and ITC regular John Carson headed the cast as Captain Britton, with Barrie Gosney and Andrew Crawford as his assistants Flight Engineer Hicks and Captain McLelland; reportedly, the three wore makeshift space helmets during recording to get an authentic sense of change in breathing for scenes where they were required to put them on or take them off. This attention to sonic detail was shared by sound effects designer Harry Morriss, who created a set of around forty effects that could be combined in different ways to lend the serial a touch of variance across its lengthy run.

Orbiter X was apparently never repeated, and was also apparently wiped shortly after its lone transmission. Following that, the series was all but forgotten about, and until recently the only mention of it on the entire Internet was on a general fifties nostalgia site. At some point, a set of BBC Transcription Services discs of the entire series were discovered at BBC Enterprises; putting it in very simple terms, these were essentially vinyl records of BBC radio shows made for sale to overseas broadcasters. Often these would have material removed or re-recorded to avoid confusing or offending overseas listeners, and a small amount edited out to allow broadcasters to fit in commercial breaks, so these recordings may not quite be what audiences thrilled to back in 1959, but the fact that they survived is remarkable enough frankly. Now they've been literally dusted down by Radio 4Extra, and have proved to be a more compelling listen than perhaps anyone was reasonably expecting.

Far from being a creaky relic weighed down by overly polite voices and laughable 'futuristic' elements, Orbiter X is a taut and believable thriller, and enough time and technology have elapsed for its quaint sounds and equally quaint theories to blast off into their own esoteric solar system. True, given that it was made not just with a different audience but with an entire different way of enjoying radio in mind, it isn't exactly what you would call an easy background listen. But it's one that rewards the small amount of additional effort and attention required tenfold, and if you blast it out from a tiny phone or tablet speaker, you can even get some sense of what it might have sounded like issuing from the 'radiogram' back in the days before Yuri Gagarin had even lifted one foot off the ground.

Orbiter X is hugely enjoyable proof that there's always something new - and good - to find hidden away in the radio and TV listings of the past, and let's hope there's more to come. Meanwhile, you may well have noticed, there aren't any radio stations devoted to revisiting the vast archive of sci-fi - or drama, comedy, documentary, soap opera, live sessions or whatever else you might care to mention - from commercial radio. Funny, that.

If you've enjoyed this, then you might also like this piece about early Doctor Who story The Sensorites.

Not On Your Telly, a collection of my columns and features which includes tons on obscure archive radio, is available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here. And there's several other books to choose from here...

It's Still A Police Box, Why Hasn't It Changed? Part Three: Su-Su-Su-Subotksy!

Although 'Dr. Who', Ian, Susan and Barbara (or, if raining, 'Louise') did nominally occupy the lead roles, recast and in canon-confounding slightly rewritten incarnations to boot, they took a back seat to The Daleks when it came to promotion. This was, after all, the height of 'Dalekmania', and Amicus Productions head honcho Milton Subotsky probably wasn't exactly thinking of the thrills and spills of The Sensorites when he snapped up the movie rights to Doctor Who.

'From the B.B.C. TV Serial by Terry Nation' - the cause of a million glib misattributions in 'sci-fi fantasy movie guides' written by clueless Americans - Dr. Who & The Daleks and Daleks - Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D. have traditionally been written off by fans as somewhere between an of-their-time curio and an embarrassing cash-in. Well, enough of that nonsense. The Dalek Films are brash, loud, colourful, action-packed, and more deserving of the average Doctor Who fan's attention than a good deal of Doctor Who itself. If your primary concern is where they fit into 'canon', then you should probably just fire yourself out of one.

That doesn't necessarily mean that everything about them was quite so spectacular, though...

They Could Have Spent A Bit More On The Opening Titles

It's scarcely worth pointing this out, but the big-screen Dalek adaptations had a great deal more money, bigger and better sets, more spectacular effects, and more colour in general to play with than their small-screen counterparts. Though you really, really wouldn't know this from their opening titles. Underneath a credit font that might as well just say 'HOORAY FOR BRITISH FILMS' over and over again, the first movie merely relies on a couple of blurry sweet wrapper-esque coloured lights pitched somewhere between the burbly mind transference effects in superlative cheapo Brit sci-fi-horror The Sorcerers and the end credits of decidedly non-superlative cheapo make-learning-fun imported animation The Wonderful Stories Of Professor Kitzel. The second, if anything, looks even worse, simply relying on a procession of slow moving vaguely tinted whirlpool-stroke-plughole effects that might actually literally be footage of paint drying. Meanwhile, the small-screen Doctor Who opening titles of the time were famously visually arresting, and had been made for virtually no money whatsoever. In fairness, the massive orchestral themes playing out over the inexcusably dull titles are somewhat on the thrilling side, but on the other hand...

What Was Going On With Those Soundtrack Singles?

Nowadays, thanks to the sterling efforts of Mark Ayres and Silva Screen, we can enjoy the splendid soundtracks to both Dalek movies in full. Back when the films were first released, though, all that music-crazed moviegoers had to remind them of the Skaro-friendly score were a handful of tie-in singles. And what peculiar tie-in singles they were. Possibly 'inspired' by John Barry's bongo-tastic break-festooned A Man Alone, Part 2 from The Ipcress File, composer Malcolm Lockyer sped up the main title theme and the Thal Ambush bit of Dr. Who & The Daleks into beat-crazy guitar'n'brass instrumental stompers, under the misleadingly sedate titles of The Eccentric Dr. Who and Daleks And Thals respectively. Less explicably still, Daleks - Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D. soundtrack-provider Bill McGuffie took the Bach-inspired piano hammering from the Cribbins-outwitted-by-jewel-thieves opening scene and fashioned it into a decidedly chart-unfriendly spot of classical/free jazz crossover called Fugue For Thought. As an impulse buy in the foyer they must have fitted the bill, but as straightforward Hit Parade contenders - which, let's be honest about it, most singles released back then very much were - they made little sense at all. However, both of these pale into rationality next to the in-character single released by Big Screen Susan Roberta Tovey. Recorded under the musical direction of Malcolm Lockyer, the Movie Doctor-eulogising a-side Who's Who? is bad enough, with its unfortunate combination of a perfectly acceptable sixties throwaway pop melody and arrangement with cloying and debatable vocal talents and peculiar lyrics about how The Doctor is "quite at home on a big spaceship/or sitting on top of a horse". Meanwhile the b-side Not So Old was doubtless written and recorded in all innocence back then, but nowadays an adolescent girl asking a fully grown man to 'wait' for her on the proviso that he doesn't tell her mother just sounds downright wrong. A pity, because it's actually not a bad tune at all. Incidentally, if you want to know more about the little-known radio spinoff from the movie, there's a huge feature on it my book Not On Your Telly. But while we're on a certain subject...

Roberta Tovey Is Actually Quite Good

If you read pretty much any article ever written about the Dalek films, whether favourable or not, you'll come away with the distinct impression that their most substantial problem is Roberta Tovey. Repositioned as a Top Juniors smartypants rather than an enigmatic otherworldly teenybopper, Movie Susan, so the literal armchair critics would have us believe, spoils everything with her shrill stage-school performance and precocious mannerisms. From this we can only deduce - as is so often the case - that they have no frame of reference outside of Doctor Who. It was pretty much an unwritten law that any British Film of the era had to have at least one chirpy, polite and adventure-happy child character hovering around the eleven-years-old mark - it wasn't as though TV Susan Carole Ann Ford hadn't occupied that role a couple of times herself, in fact - and as they tend to go, Roberta Tovey is a lot more restrained, likeable, expressive, and capable of delivering dialogue in a manner that suggests she may even have read something aloud at some point in the past. Alright, so she's hardly exactly operating on a Whistle Down The Wind level, but nor is she worthy of swelling the cast of Our Mother's House either. And while we're taking down the main points of scoffing-fuelled attack on the movies...

The Dalek Smoke Guns Are Also Actually Quite Good

Whether the original plan for them to be armed with flamethrowers was vetoed on health and safety grounds, or because it would risk terrifying the juvenile audience (which seems a bit incongruous given that the TV Daleks were OP-ER-A-TING-PYRO-FLAMES left, right and centre), the Movie Daleks ended up spraying Peter Cushing and company with huge blasts of exterminating steam courtesy of their controversial 'fire extinguisher' attachment. Conventional fan wisdom would have you believe that this was a cheap and nasty compromise, which looked little short of embarrassing next to the simple but effective negative image gambit deployed on the small screen. Once again, if you consider the movies in their proper context as standalone sixties British Films, as opposed to charging at them with your Doctor Who gloves on and waving a copy of The Unfolding Text, it all starts to seem a lot more favourable. Cinema audiences needed a big sound and a very visible effect to go with it, and the skilful direction actually gives the off-the-cuff replacement for a familiar effect the illusion of a dangerous weapon. They may fire vapour rather than concentrated light as a needs must measure, but it actually adds a distinct atmosphere to the bigger, bolder and brighter Dalek films. Of course, though, not everything seen in the films was quite so different from their television counterparts...

They Like Big Butts And They Cannot Lie - Now On The Big Screen In Colour!

We've already looked at how, presumably courtesy of cameramen angling to hook themselves a gig on Top Of The Pops, mid-late sixties Doctor Who had a disconcerting habit of zooming in on female cast members with sizeable backsides. And rest assured that there is plenty more - and plenty worse - to come. Needless to say, the films did not let the side down in this, erm, area, notably with poor old Film Barbara Jennie Linden being forced to squeeze herself into a circulation-threateningly tight pair of pink trousers, and directed to continually thrust her arse in the direction of the all-too-eager cameramen, almost as if it had been specified in the script. Not to be outdone, her Daleks - Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D. replacement Jill Curzon opted to capitalise on her new-found fame by stripping down to her bra and pants and draping herself all over a Dalek in a somewhat racy-for-the-time photo session. Terry Nation's thoughts on this blatant misuse of his creations are sadly unrecorded.

And, funnily enough, that's not the only dubious production detail of the television version to find its way into the films...

The Stock Footage Invariably Looks Awful

Alright, this is a bit of a misleading heading, as there's only really one piece of stock footage between the two movies. But what a glorious mismatch of film stock it is. Right at the end of the first film, Ian opens the Tardis door onto an off-screen adventure that will probably have 'canon' obsessed fans... well, they never are going to give up and go home, are they? Anyway, he opens the door onto bought-in film of advancing Roman Centurions, apparently giant-sized and abiding by an entirely different colour spectrum, who march straight through the Tardis exterior without even drawing breath. It's a fun way to end the on-screen action, but even to audiences back then it must have looked every bit as jarring as every last second of muddy and battered film of clouds that they could get to see in black and white and for free at home. And although it's not quite the same thing, a special mention here for the sore thumb-like use of toy Daleks in the second movie's climactic explosions.

In case you hadn't worked out from the above, Movie Ian is a lot less rational and practical and a lot more comical than his small-screen counterpart, and sometimes they take that a bit too far...

What Box Of Chocolates Ever Made A Noise Like That?

During Ian's zanily clumsy on-screen introduction, there's a scene in which Roy Castle is called upon to accidentally sit down on the box of chocolates he had brought as a gift for Barbara, while Dr. Who and Susan look on in bemused despair. There's nothing wrong with this scene in itself, not least because it's played with decent comic timing from all concerned, but the real issue is with the sound effect used to denote the chocolates being crushed; a loud splintery crash. This is all the more ill-fitting given that the assembled company have only just made a bewilderingly big deal of the fact that they are in fact SOFT centres ('Barbara's Favourite', apparently). Unless Terry's were planning to introduce their hastily-cancelled Balsa Wood Assortment as a tie-in with the film, we'll just have to chalk this up to the exuberance of sixties filmmaking. Speaking of which, despite what the others keep saying, it's not actually Ian's fault that the Tardis accidentally takes off and ends on Skaro - he's knocked over by an over-affectionate Barbara, who keeps conveniently quiet once blame starts being apportioned. And while we're on the subject of things being broken by Ian...

The Other 'Monsters' Look Rubbish Compared To Their TV Versions

In-house BBC staff designer Ray Cusick may have infamously lost out on his chance to share in the Dalekmania Millions due to tedious contractual reasons, but he was clearly able to prevent Subotksy and company from using certain other of his designs. How else would you explain the fact that The Magnedon, the creepy, spindly fossilised metal reptile that the Tardis crew find on first venturing out into the petrified forest, here becomes a sort of multicoloured dog with a ruff on. Or that the creature in the Lake Of Mutations - never exactly the best realised of alien menaces in the first place - is barely even visible at all. Still, what can you expect when the planet's dominant life form simply pops down to their local Habitat for their hi-tech scientific equipment...

Why Do The Daleks Have So Many Lava Lamps?

On the whole, the Dalek city and flying saucer sets in the two films are pretty impressive. The eye-cameras mounted on the walls look sinister and oppressive, the automatic doors open and close convincingly (even if Ian does decide to mount a low-budget recreation of the video for Glory Of Love with them for some reason), and even the signs saying 'WASTE DISPOSAL' make sense if you interpret them as being there for the benefit of the Robomen. The only jarring note is that the Dalek labs are positively groaning under the weight of Lava Lamps. And not incorporated into the design either, just free-standing on any available bare-looking surface. Given that Lava Lamps had been commercially available for over two years by that point, they can't even be explained away as having been 'new' at the time, and frankly it just smacks of cheapness in an impressively expensive-looking franchise. Then again, The Daleks did appear to be using those static lightning plasma globes as a key piece of equipment in 1988's Remembrance Of The Daleks, so novelty ornament gadgets were clearly of enormous technological importance to them. Don't be surprised if when The Power Of The Daleks finally turns up, there's a scene featuring them playing with those spidery octopus things that rolled down windows.

There's Never A Postmodern Policeman Around When You Need One

Mention Daleks, the mid-sixties and the so-called 'fourth wall' to the average Doctor Who fan, and chances are that the first thing they think of will be William Hartnell's bafflingly contentious toast to the viewers at home on Christmas Day 1965. A more alarming and incongruous travel in hyperreality occurs, however, immediately prior to the opening titles of Daleks - Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D.. Keen to report the 'smash and grab' to the local bobby, a cheerful down-to-earth honest-to-goodness-guvnor geezer in a flat cap and mac hurls himself bodily at the nearest Police Box, only to find himself falling right through the dematerialising Tardis. Apparently used to this sort of thing happening, he turns to the camera and looks straight at the audience with a shrug and a comically exasperated expression. Quite where that now places the films in accepted Doctor Who 'canon' is anyone's guess...

...but next time, we're back to the series itself, so join us then for a 'Galaxy Accident', a Twitter War with @maaga_, and Dodo swapping fashion tips with Roy Wood...

If you've enjoyed this, then you might also enjoy this piece on early Doctor Who story The Sensorites.

You can find an in-depth article on a little-know BBC Radio version of Daleks - Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D. in Not On Your Telly, available in paperback here or from the Kindle Store here.

Diggin' The Dankworths

George Martin. Joe Meek. The BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Nowadays you'll find cheerleaders for just about every once-overlooked Brit-based sonic pioneer of the pre-Rubber Soul era, and rightly so. Even Freddie Phillips and his Trumptonshire-traversing hammer-ons, though in fairness you'll probably actually have to read something written by me to find that.

But who's singing - doubtless with over-elaborate vocal extemporisation - the praises of Johnny Dankworth and Cleo Laine? Well, given that the general public's entire image of them seems to be based on The Two Ronnies impersonating them every single week with jokes seemingly based on two other performers altogether, probably very few people. So it's time to put a stop to that nonsense. Before they settled comfortably and deservedly into middle-bit-of-Pebble-Mill-At-One ubiquity, Johnny and Cleo were amongst the first to mess around with concept albums, global rhythms, pre-synthesiser electronic keyboards, sound effects, multimedia, reverb, spoken word comedy bits and much more besides, most of it in glorious mono to boot. So join me as we take a stroll through some of the highlights of their jaw-droppingly prolific early output, all of which is almost as exciting as The Exciting Mr. Fitch himself...

Experiments With Mice (1956)

Soundtrack Music From 'The Criminal' (1960)

A no-holds-barred look at prison life starring Stanley Baker as an inveterate pilferer with a penchant for racecourse cash boxes should usually call for frenetic Crime Jazz, and that's exactly what we get here with the likes of the swaggering Riverside Stomp and the alarmingly haphazard Freedom Walk. Those in search of the full experience will also be wanting Cleo's moody theme song Thieving Boy, with remorse-lust lyrics co-penned by none other than Alun Owen, which was released as a standalone single backed by Let's Slip Away, her more wistful and optimistic curtain-raiser for the same year's big-screen version of Saturday Night And Sunday Morning. It's also worth noting that this soundtrack dates from Dudley Moore's brief spell with the Johnny Dankworth Big Band, which doubtless proved a source of great amusement to Peter Cook.

African Waltz (1961)

The EP of the Big Pop Hit, featuring not just the shrill 3/4 foot-twisting top ten smash title track, but also percussion-hefty Mod dancefloor filler Chano, swaggering Soul Jazz slow-groover Moanin', and the original version of the original theme tune from Honor Blackman era The Avengers. Although it's hardly on the same level as Laurie Johnson's subsequent more celebrated Steed-accompaniment (though, to be fair, few TV themes actually are), only the most blinkeredly cloth-eared of Popular Beat Music-averse Archive TV obsessives could realistically deride it as a load of old rubbish. And unfortunately, there are a lot of them out there. Still, some decidedly more funky types clearly thought it was something approaching lost fabness...

What The Dickens! (1963)

With the aid of an all-star horn-honkin' line-up including Tubby Hayes and Ronnie Scott, Johnny takes an impressionistic instrumental trip through the collected works of Charles Dickens, improvising across the pages of The Pickwick Papers, The Old Curiosity Shop, Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol and David Copperfield, though sadly there was no accompanying EP based on Sketches By Boz. Inspired by the 'feel' of the source novels, it's like the soundtrack to some sadly non-existent Swinging Sixties-era Dickens biopic, with highlights including catchy street-saunter Little Nell, and Pickwick Club, which is so warm and quirky that you can just imagine Tupman and Snodgrass taking their boots off in front of a roaring fire with hilarious social faux pas consequences. It's probably more useful than the average A-Level Study Guide too.

Shakespeare And All That Jazz (1964)

Not to be outdone, Cleo also turned her hand to the exciting new world of Literary-Jazz crossover, and came up with an entire album's worth of adaptations of Iambic Pentameter into Iam-bee-ba-ba-doo-bah-be-dah-dic Penta-mah-da-doo-da-de-dam-eter. The Bard may only have been the fifth greatest wordsmith of history (after Dickens, Douglas Adams, PG Wodehouse and Richard 'Skinhead Escapes' Allen), but this is every bit a worthy companion piece to What The Dickens!, with highlights including the surprisingly riqsue (well, by 1964 standards) It Was A Lover And Her Lass, Scottish Play-summarising breathy Jazz Cellar epic Dunsinane Blues, and the suitably chilly Blow, Blow Thou Winter Wind. Much beloved of English teachers desperate to prove to their charges that they were still 'with it'.

Beefeaters (1964)

Originally composed and recorded as the theme for long-forgotten ITV X Factor template Search For A Star, a talent show that reportedly discovered future Doctor Who companion Wendy Padbury, this wild jazz stomper was later picked up as theme music by a certain Pirate Radio DJ, and - with the judicious addition of 'barks' from Arnold The Dog - subsequently became, as over-literal hern-ing bores will never tire of pointing out to you, technically the actual first record heard on Radio 1. Which makes it something of a weird coincidence that the not-that-dissimilar b-side was entitled Down A Tone.

Sands Of The Kalahari (1965)

Only two tracks were released from the soundtrack to cinema's most edge-of-the-seat baboon-plagued desert trek, but what tracks they were. The massive-sounding yet inappropriately jaunty title theme waltz is pretty much the musical embodiment of a time when British Cinema could do no wrong, while the moodier and more reflective flip Night Thoughts showed up in a key scene but was perhaps still, erm, a little too jaunty for the on-screen action. You'll find the movie itself on Film4 every couple of minutes, but unfortunately there's still no sign of a release for the full score.

Little Boat (1965)

More 45-only action (though the a-side later appeared on the fabulously 'Pipe Down, Blokes'-themed album Woman Talk, which you can see the fantastic cover of below); Cleo's chart-scraping translation of Bossa Nova favourite O Barquinho is fab enough, but it's the b-side you should really look out for, with its percussion-rattling piano-smashing ode to the charms of some heart-fluttering cocktail-swilling ski-jumping Jeff Winger-esque aesthete who apparently has his own personal brass band to fanfare his entrance, but not any tangible hint of a first name. All in all, not altogether surprising that this didn't make it to the album...

The Zodiac Variations (1965)

While Cleo was musing on gender-politic rumblings, Johnny got a bit cosmic with this set of twelve impressionistic Late Night BBC2-friendly instrumentals based on the purported characteristics of the dozen chronological subdivisions of everyone's favourite dupe-fleecing hokum. From his musical findings, we can deduce that while Librans like to chill out with a hefty book and a good strong coffee, Aquarians are rather more fond of doing a dance in front of a mirror with a glittery top hat and cane. Though I would say that, being a Taurus. TV's Catweazle will mayhap be pleased to hear that this rotating plastic demon also includes a 'thirteenth' star sign sign in the form of ecliptic-straddling medley Way With The Stars.

The Idol (1966)

We're heading into the sadly all-too-brief Golden Age of Dankworth/Laine film soundtracks now, with this obscure number starring Michael Parks as a pranksterism-friendly hip'n'happenin' art student with a 'thing' for whatever they called MILFs in 'old money', and John Leyton as a disapproving best friend/son. Not quite the lost classic that it might sound, if we're being honest about it, but the frug-tastic party scene-friendly musical contributions deserve a bit more exposure than the film itself.

Modesty Blaise (1966)

She'll turn your head, though she might use a judo hold! One of cinema's most glorious psychedelic messes scorches the projector when Monica Vitti puts in an impenetrably-accented turn as the pulp paperback spy as she shags, hallucinates and assassinates her way across Europe, in pursuit of some stolen diamonds that haven't actually been stolen yet. Nosebleed-inducing pop-art mayhem with a soundtrack to match, from the ridiculously camp and overblown title song featuring the vocal talents of long-forgotten pop hopefuls David And Jonathan, to the overdriven wasp-trapped-in-Farfisa thrills of The Willie Waltz. The sort of film that can nowadays get you No-Platformed for liking it, though in mitigation the b-side of the single version of the main theme features the more politically acceptable strains of the swaggering vibe-heavy blare that introduced The Frost Report, the perfect accompaniment to David Frost holding up a microphone to a Keep Left sign and doing a 'sceptical' face.

Fathom (1967)

And if you weren't quite tutting enough yet, get a load of Raquel Welch as a military skydiver in an impressively cantilevered lime green bikini, trying to recover a stolen nuclear detonator whilst dodging a bull intent on stealing her bra, and Richard Briers occasionally saying some lines in the background. This all a tad more subdued, sultry and samba-tinged than the walloping Modesty Blaise score, but somehow you get the impression that the music wasn't really one of the most prominent points here.

The $1,000,000 Collection (1967)

It wasn't just pop that went a bit psychedelic over the summer of 1967, and here Johnny treats us to a series of Prog Jazz-anticipating 'sound paintings' inspired by his favourite pieces of pricey modern art. It's a strangely under-acknowledged fact that the UK Jazz community were the most enthusiastic and profligate patrons of the pop artists, op artists and photorealists, and Johnny and Cleo actually owned Derrick Greaves' Two Piece Flower, as seen on the album's cover and sketched out here in a catchy experiment with plucked strings. Also well worthy of their purported price tag are the kaleidoscopic sleighbell-underpinned frost-on-the-windows salute to Thomas Kinkade's greetings card-esque Winter Scene, and a Late Night Line-Up-evoking beatnik jive rumination on Modigliani's Little Girl In Blue, which is certainly more cheerful than her miseryguts expression should warrant.

Off Duty! (1969)

The Prog Jazz leanings continue with an album of covers of recent genre favourites including Charlie Barnett's Skyliner and Gerry Mulligan's Bernie's Tune, alongside an alarming reworking of African Waltz and the blaring Dankworth-composed American sitcom theme-esque mini-suite title track. Also on board is a seriously funky reworking of Holloway House, an early effort from little-known piano-pounding jazz trio leader Laurie Holloway, later to furnish many an ITV Saturday Night Light Entertainment show with a near-identical theme boasting the exact same eight-note ending as each other.

Portrait (1971)

Cleo treats us to interpretations of a handful of her recent soul and jazz favourites, amongst them a soaring rampage through Aquarius, a peculiar bit of architectural satire on Model Cities Programme, a reworking of Bossa Palma Nova from the Fathom soundtrack, and best of all, a rip-roaring blast through Northern Soul stomper Night Owl. Snorted at by purists, apparently, presumably while spinning round and not having much imagination.

Lifeline (1973)

We're now in proper full-on Test Card Funk territory as wah-wah guitars and slap bass wallop their way across the stereo mix, and the entire second side taken up with some sort of suprious Journey To The Shopping Centre Of The Earth-style musical narrative, which is really just an excuse to indulge in some seriously heavy extended grooves. Meanwhile, over on the first side you'll find Johnny's legendary theme for Tomorrow's World, a tune so aware of its own brilliance that it takes an entire three opening fanfares and a Hammond Organ voluntary before it sees fit to properly get going. Also worthy of note is the accompanying non-LP single Bitter Lemons, featuring a wonky Sly Stone-inspired groove underpinning some abrasive trumpet that appears to be being played underwater.

Movies 'N Me (1974)

An updated re-recorded rifle through Johnny's soundtrack back catalogue, taking in extracts from deleriously obscure sixties Brit Movies like Darling, The Servant, Return From The Ashes and more, including the first ever outing for his main title for controversial gorilla suit-facilitated mental breakdown comedy Morgan: A Suitable Case For Treatment, sadly still not available in its original form (though the contemporaneous cover by Manfred Mann's Mike Vickers is well worth checking out). The break-festooned whipped-up-tempo take on Modesty Blaise was later sampled by Gorillaz, but the real highlight is Look Stranger, his inappropriately funky theme for BBC2's long series of grainy ruralist-pluralist documentary films about beardy blokes in coastal towns lamenting how they don't make them new-fangled fishing nets like they used to or something. Who'd have thought it? For a similar discrepancy between theme music and on-screen action, see Telford's Change, released as a single by BBC Records And Tapes around this time (and also covered in Top Of The Box!).

MISSING IN ACTION...

Johnny's utterly bonkers theme from early seventies ITV children's show The Enchanted House, a maddeningly catchy yet disconcertingly topsy-turvy tune welded to a wall of tuned percussion. You can read more about The Enchanted House in my book Not On Your Telly, but the show itself hasn't been seen anywhere since the early eighties, and even the trebly recording of the theme that was on YouTube seems to have disappeared now...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)